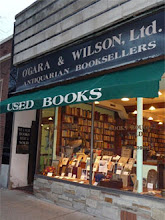

What reminds me of childhood, you ask? This:

I can't quite recall when I discovered James Thurber, but I do believe The Thirteen Clocks was the first book of his that I read. It amazed me with its eccentric and exuberant humor. I discover from this biography (click here) that much of this eccentricity comes from his mother:

Mary Thurber was a strong-minded woman and a practical joker. Once she surprised her guests by explaining that she was kept in the attic because of her love for the postman. On another occasion she pretended to be a cripple and attended a faith healer's revival, jumping up suddenly and proclaiming herself cured. Thurber described her as "a born comedienne" and "one of the finest comic talents I think I've ever known."

This First Edition of The Thirteen Clocks features glorious illustrations by Marc Simont:

As for an actual description of the book ... well, I can start by saying that I tend to feel slightly irritated by most comic fantasy. The Princess Bride is a fine work, as is Patricia C. Wrede's more recent Dealing With Dragons, and many things Terry Pratchett has written; but most comic fantasy follows the same tired tropes, and has all the same self-conscious, contrived elements. The Thirteen Clocks is comic fantasy that's not only far, far better than those tropes -- it's completely different from everything I mentioned above. It involves a prince seeking the hand of a princess, etc., but in its self-consciousness and random asides, it's charming and ironic rather than tired. If you've never read it, you're in for a treat -- and if you already love it, then how can you resist buying this excellent copy (at $40.00)? Did I mention that this is not only the First Edition, but the thirteenth printing?

All right, I've rambled on about my childhood enough. Time to showcase some early 1900s nostalgia instead, with this week's Collector's Item:

Stereography is one of those technologies that, with the advent of film, quickly fell out of favor (I was surprised to see that there are still stereography devotees, and even websites devoted to stereography!). Back in their day, stereoscopes were a wildly popular method of viewing faraway vistas or other exotic things. The viewer would hold the stereoscope before his eyes like this:

... and insert one of the cards into it:

When viewed through the viewer, the cards have a sort of pop-out effect, creating a limited three-dimensionality. And each of the cards has a long description of the scene it's portraying on the back; for instance, the Campanile Doge's palace and prison card from Venice starts with, "We are on a broad lagoon," and goes on to spend three paragraphs talking about the canals of Venice, the general appearance, and the history of the buildings on the card.

Here in the store, we sometimes sell stereoscope cards on their own, but in this case we've got a full set plus viewer on our hands. We've even got a 1926 book that goes with it:

The book would be better titled In Praise of the Stereoscope, as it mostly discusses the invention of marketing of said item, but it does have a bunch of card captions. And the red pamphlet is three maps -- one of New York, one of Washington D.C., and one of the world -- all in beautiful condition despite their age, and all intended to help stereographers find the locations on the cards.

We're selling all these things together, for $200.00. The 113-card collection, as you can see from the "spines" of the faux-book card case, is themed "Tour of the World" -- how very Victorian -- and each card provides a landmark like Westminster Abbey, or an everyday scene like the gondolas in Venice, or an exciting ruin from faraway lands. Well, I suppose Westminster Abbey is "faraway lands" for us Americans, but ... onward to the next item.

That is, this Affordable and Interesting pamphlet, somewhat utopian and hilariously titled:

Lorenz Stucki has Views (I think the capital V expresses his seriousness) on how humanity has undone itself with modern society. He first writes a paean to a potential world full of robots, where no one might need to work and everyone might pursue the arts, then sighs that modern society is so obsessed with work that we are unable not to work. In fact, when we aren't working, we become neurotic horrible people, or aimless and depressed! He blames society for this, and concludes that though we ought to create a high-leisure society, we also ought to properly educate its members such that they spend their time doing the Right Things: art, obviously, along with the refining of our virtues. (Stucki doesn't really explain what this latter part means.) I would like to believe that humanity, given nothing but leisure, would spend all its time on art if "properly educated" to do so, but I suspect that equal portions of time would be devoted to gossip and beer. Of course, I could be wrong. Or we could elevate beer and gossip to an art form ... that works too, I suppose. Buy the pamphlet and form your own Stuckian theories for $6.00! *

Well, I'm off to dinner. Maybe I'll refine the art of gossip while I'm there. You do your part, gentle readers, and perhaps we can write a manifesto for the gossip movement next week!

* In the incredibly unlikely event that Lorenz Stucki reads this: Dear sir -- this is all in fun, and no offense is intended.

No comments:

Post a Comment