Dear Readers,

I sincerely hope the whirlwind of changing blog authors and new employees has not been too dizzying. That said, I must introduce yet another member of our staff. His name is Jerome.

As you have no doubt guessed, Jerome is a monk. He can be seen in this photograph working hard on the ledgers, meticulously copying columns of records in order to... Hold on a moment. I hear a faint voice calling from the back of the store.

Sorry about that. Jerome has informed me that he tires of his mindless drudgery, hour upon hour of the same boring tasks that occupied him at the old Scriptorium. I offered to let him write this week's blog, and he seemed greatly cheered by the prospect. My apologies if the writing is dry or the topic dull. Without further ado...

Dull? Dry? He's got some nerve, that Alan, implying we monks sit around all day discussing how many angels can fit on the head of a pin, or debating the intricacies of Trinitarian doctrine. I'll give you readers a, what do you call it, an Internet Grog, I think Alan said, that's both educational and stimulating.

In fact, speaking of grog, you should know that many monks like myself specialized (and still specialize) in the brewing of beer. We've been a fun-loving bunch for ages. Hopped barley beer first appeared in the charter of a Benedictine abbey in 768. Water was often contaminated, and beer provided a safe alternative beverage, since boiling is a step in the brewing process. The quality of this fine product improved generation after generation, and eventually brought fame to monastaries. Over 500 monastic breweries existed by the year 1000, producing beer both for sale and consumption by their members (a slightly weaker version was even developed for nuns). Of course, some stick-in-the-mud monks have tried to curb this habit -- pun observed but unintended. In 1664, the Abbot of La Trappe felt things were getting a little too liberal, and passed the Strict Observance, permitting only water to be drunk at the monastery. Needless to say, righteous monks like myself were loath to comply, and I have it on good authority that many disobeyed the regulations and continued to brew tasty beer in secret. This is no longer necessary, thank goodness, as the rules have been relaxed considerably since then.

Ironically, monastic beers experienced an explosion in popularity and quality during the 1920's and 30's, precisely when this nation enacted its own Strict Observance. Of course, if monks were unable to desist from beer making and drinking, Americans were even less likely to do so. Alcohol thrived during Prohibition, and the main character in this week's Collectible was accused of making his fortune in bootlegging.

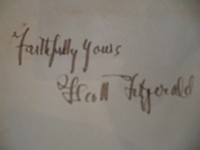

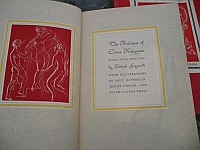

Jay Gatsby -- monk at heart? Alan has been reading over my shoulder, and insists I mention the fact that this is a first edition of The Great Gatsby. Of course, at the Scriptorium, all editions were first editions, since they were copied by hand, but that's another matter. So there you have it, a first edition of the Great Gatsby, excellent reading for those who are interested in life during America's time of Strict Observance. Needless to say, F. Scott Fitzgerald did not observe strictly. He was a heavy drinker, and it interfered severely with his writing later in life. In fact, if you look closely at the photograph below, you might see a slight shakiness in his signature.

Yes, that is F. Scott Fitzgerald's signature, in a copy of his Flappers and Philosophers. These two books are priced at $1950 and $6500 respectively. Drink some good Trappist ale and perhaps you'll be less reticent to make the purchase.

If your tastes run more towards beer than literature, as mine do, you will probably be tempted by the Affordable and Interesting items this week.

Practical Points for Brewers was published in 1933, the year that Prohibition ended. Along with this fine volume there are scores of advertisements, pamphlets, beer-brewing manuals, and other printed material of related interest available for purchase. Prices range from $5 for one page ads to $75 for the scarcer books. They provide a wonderful window into the world of early 20th century American beer and alcohol. Personally, however, I wouldn't use the reference materials to actually brew beer -- I borrowed one of the volumes, followed the instructions rigorously, and came up with some pig-swill that I wouldn't wish on the man behind the Strict Ordinance. A friend of mine said it tasted a good deal like Miller High Life, which makes sense -- in 1933, Miller dispatched a case of said beer to President Roosevelt, celebrating the repeal of the 18th Amendment. Knowing this makes me feel better, since it means the poor quality was the fault of the method, not the brewer. Alan is again reading over my shoulder, and wants me to add that the thoughts and opinions expressed in this grog (sorry, blog, I'll get it straight from now on, thanks Alan) belong solely to the author. Alan himself is a fan of Miller High Life.

With all this talk of alcohol, and the mention of Mr. Fitzgerald, it is fitting to mention one of the most eloquent testaments to the beauty of drinking, though The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam concerns wine, not beer.

Translated by Edward Fitzgerald, the poem beautifully twines drinking and living: "So when that Angel of the darker Drink / At last shall find you by the river-brink, / And offering his Cup, invite your Soul / Forth to your Lips to quaff -- you shall not shrink." I shall not shrink, thank you very much. This particular edition, and the Favorite of the week, combines my greatest loves -- good drinking, divinity, and quality bookmaking. Peter Pauper Press produces quality, affordable books ($6.00 for the one pictured here). Interestingly, despite his fame as a translator of this poem, Edward Fitzgerald did not resemble the later F. Scott in his actual drinking habits -- in fact, he was a vegetarian who destested vegetables, and subsisted entirely on a diet of bread, fruit, and tea. Perhaps he didn't pay close enough attention to the meaning of what he was translating -- a mistake often made by scholars.

No comments:

Post a Comment