Dear Readers,

The focus of our current blog is a topic close to my heart – the illustrated book. There is no question, of course, that certain types of books benefit from illustrations. One shudders at the thought of a cookbook entirely bereft of pictures, and an art-book without some reproductions of the works it treats seems, at least to me, entirely pointless. But the relative value of illustrating fiction is not so easily decided. Tolkien himself, in his essay “On Fairy-Stories” complains that illustrating such tales deprives children of the opportunity to imagine things for themselves. This, of course, from an author who illustrated the Hobbit himself. While Tolkien doesn’t count the Hobbit as a fairy-story, it seems plausible to extend his argument to all illustrated fiction. Somehow, the act of reading is essentially an imaginative one, and illustrations restrict the reader’s freedom, imposing particular images onto the blank canvas of the text.

I’ve heard people make similar claims about movies – Christopher Tolkien wanted nothing to do with the film adaptations of the Lord of the Rings, saying they were peculiarly unsuited to film, and his father has been quoted as hating all things Hollywood. After watching the cinematic form decimate favorites like The Phantom Tollbooth and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, some might be inclined to agree. But the issue is more complicated than that. Certain books might be bad material for film adaptation. Others, like Gone with the Wind, Pride and Prejudice, and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, do quite well, in my opinion. There is, I think, no standard rule to be applied in this case. Plays, needless to say, are actually meant to be performed – with Shakespeare or Beckett we should have no compunctions about restricting the reader’s imagination with a movie or performance, since the reader is actually meant to be a spectator. A book that has been singled out as impossible for adaptation (Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, for instance), is simply waiting for a talented film-maker to rebut the claim.

So when should something be illustrated, and when should things be left to the reader’s imagination? Do the same rules apply – can a good illustrator always rebut the claim that a book ought not be illustrated? Perhaps. But maybe a different place to start is the general consensus on which audience benefits most from illustrated books. The answer is easy: children. Modern novels tend not to be illustrated – children’s books almost always are. Indeed, the amount of illustration in a book is inversely proportional to the target age group. (Imagine Dr. Seuss without illustrations!!)

At first this trend might appear intuitive. Kids like pictures. They need them to supplement necessarily sparse narratives, and peak their curiosity. Or do they? “When we are very young children we do not need fairy tales: we only need tales. Mere life is interesting enough. A child of seven is excited by being told that Tommy opened a door and saw a dragon. But a child of three is excited by being told that Tommy opened a door. In fact, a baby is about the only person, I should think, to whom a modern realistic novel could be read without boring him.” G.K. Chesterton makes a wonderful point. Children have vibrant imaginations, lacking in most adults, it seems. Not only that, but our modern attention span has dwindled to a pathetic shell of itself – just look at the length of camera shots in recent movies compared with those of a couple decades past. One could make the case that it is adults who need illustrations to help them imagine things more vividly, especially given the rather dry content and increasing length of the reading material they tend to choose.

You may, at this point, be starting to lose patience. It is my hope, in fact, that you are thinking, “All right, all right, enough already. Where are the pictures of the books? That’s why I read this blog.” Because if you are, it would make my argument that much more compelling. The interest of this blog lies in part with the inclusion of pictures, which spruce up the otherwise dreary procession of letters that currently clog your screen. So without anymore boring, intellectual, adult-oriented prose, I offer three books for your consideration. All are illustrated, and they cover a wide enough variety of target audiences for any interested blog readers to come in and settle this question for themselves.

Collectible

.

.

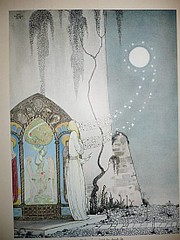

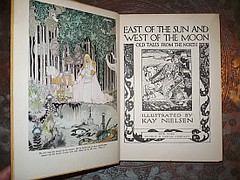

Book: East of the Sun West of the Moon. $200. Target audience: Children (and wealthy adults). Illustrator: Kay Nielsen. One of three greats from the golden age of book design and illustration (Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac are the other two). He is my favorite of the three, due to his pronounced Asian influence and particular skill with line drawings. This book of Norse fairy tales showcases, I think, his best work. Absolutely wonderful example of the lavish gift books produced during the first half of the 20th century.

.

.

.

.

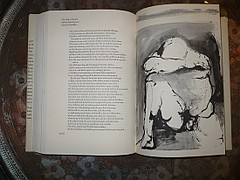

Book: Gulliver’s Travels. $7.50. Target audience: Adults? Children? Illustrator: Luis Quintanilla. Manifestly a book for adults, the fantastical elements of Swift’s “frank and vitriolic satire” (from the dust jacket) are now popularly targeted at children (in abridged editions, a topic for another blog…). Almost every page of this edition is profusely illustrated with Quintanilla’s hilarious black and white prints. A stunning example of graphic art, at a remarkably affordable price.

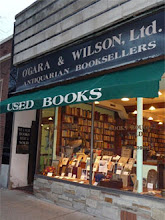

There you have them. Say whatever you like about the relative merits of book illustration, but make sure your opinion is educated, preferably through a visit to our store.

From O’Gara and Wilson, this is Alan, over and out.

No comments:

Post a Comment